Equine piroplasmosis

Babesia caballi (B. caballi) and Theileria equi (T.equi) are obligate intraerythrocytic protozoan parasites that cause equine piroplamosis. Previously, T. equi was known as Babesia equi. These parasites are transmitted by ticks of the genera Dermacentor, Hyalomma and Rhipicephalus. Ticks become infected by ingesting these protozoan which are in the blood of infected horses. Horses that survive can become inapparent carriers for a long time and they are a source of infection for the ticks which will parasite more horses. Besides, mainly in the case of T. equi, placental transmission is possible. Foals can be born with severe anaemia and icterus and die a few days after their birth or they can be born as carriers without clinical signs. Equine piroplasmosis is important since it is the main restriction on the export of horses to other countries.

The clinical signs of equine piroplasmosis are variable and non-specific. In general, the infection with T. equi results in more severe clinical disease than the infection with B. caballi. Signs of acute infection can vary from fever, anorexia and labour breathing to anaemia, thrombocytopenia, icterus and petechiae in the conjunctiva. Chronic infection may result in weight loss, lethargy and partial anorexia, and the spleen might be enlarged on rectal palpation.

How can we diagnose equine piroplasmosis?

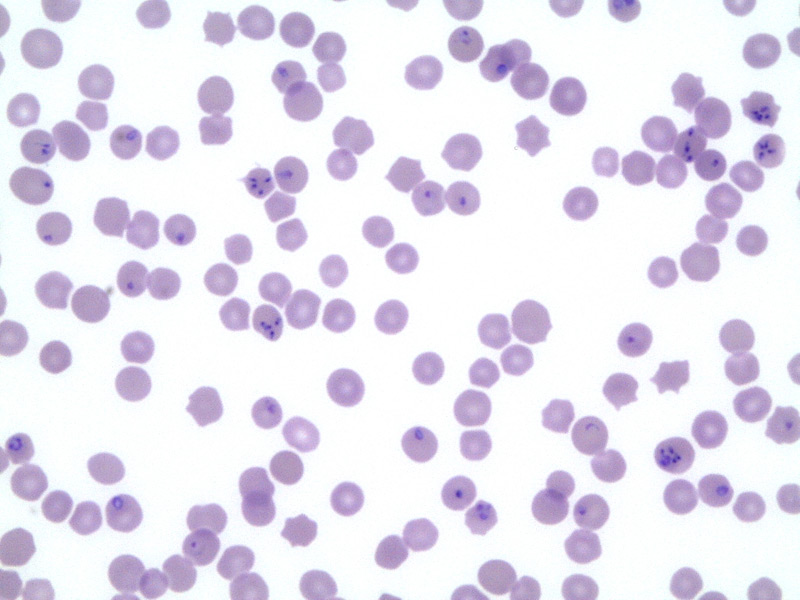

During the acute state of the infection, equine piroplasmosis can be diagnosed through a thin blood smear stained to identify the organisms within the erythrocytes. But this method has a low sensitivity because the percentage of parasitemia is very low, even in severe infections, especially in B. caballi infections.

Several serologic tests have been developed to increase diagnostic sensitivity. These test include the complement fixation test (CFT), indirect fluorescent antibody test (IFAT) and competitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (c-ELISA).

CFT can detect seroconversion approximately 8 to 11 days after infection. CFT is a very specific test yet lacks sensitivity in chronic or inapparent phases of infection; therefore, CFT should only be used in cases of acute infection. Cross-reactivity between T. equi and B. caballi antibodies when using the CFT has been documented.

The IFAT is only recommended in acute phases, although it is considered more sensitive than the CFT and the titers were more consistently detected and remained elevated longer with the IFAT versus the CFT. IFAT can detect seroconversion 3 to 20 days after infection and it is often used as a complementary test to aid in the interpretation of CFT and cELISA results.

The cELISA is considered to be the most sensitive test for chronic or inapparent infection, detecting seroconversion 21 days after infection. For this reason, the cELISA represents the gold standard method for the detection of carrier horses.

Furthermore, PCR is a very sensitive test and is used for the detection of parasite DNA isolated from the peripheral blood of an infected horse. However, it has been demonstrated that after the treatment the animal can be PCR negative but cELISA positive for 24 months after the clearance of the parasite.

To summarize, the protocol for the diagnosis of a horse with clinical signs compatible with equine piroplasmosis (acute disease) would be the following:

- Hemogram and microscopic observation of a blood smear.

- PCR (real time) for Theileria equi and Babesia caballi.

- Paired serology (first sample at the onset of clinical signs and second sample drawn 14-21 days later) by CFT or IFAT.

Finally, in order to diagnose a carrier without clinical signs, and also for the pre-purchase examination of a horse prior to exportation, the ideal test for the diagnosis of equine piroplasmosis is the c-ELISA.

Treatment and control strategies.

T. equi infections are typically more difficult to treat than B. caballi infections. T. equi can stay within the infected animal until 24 months after the treatment, whereas in a B. caballi infection this time varies from 3 to 15 months.

Several drugs have proved to alleviate clinical signs, being imidocarb dipropionate (ID) administered intramuscularly, together with a correct hydration of the animal, the most effective. ID has anticholinesterase activity, so reactions to the drug as sweating, signs of agitation, colic and diarrhea are often present.

Other drugs used against equine piroplasmosis are diminazene aceturate and diaminazene diaceturate, but upon administration they can cause severe muscle damage. The antibiotic oxytetracycline administered intravenously is effective against T. equi, but not against B. caballi. Finally,buparvaquone is no longer commonly utilized in practice.

Regarding the control strategies, there are no vaccines available for these parasites. Disinfectants and hygiene are not effective against spread of tick-borne infections. However, avoiding the contact with ticks by using acaricides is essential. A regular evaluation of the animal and removal of the ticks can help to prevent the infection.

For further information and any questions regarding the diagnosis, treatment or control of equine piroplasmosis please contact:

Equine Health Surveillance Unit

VISAVET Health Surveillance Centre

Complutense University Madrid (Spain)

Tel.: (+34) 913944096

seviseq@ucm.es

Bibliography

- Anon. 2010. Piroplasmosis equina. The Center for Food Security and Public Health and Institute for International Cooperation in Animal Biologics, Iowa State University.. 167(1-2): 50-60.

- Bruning A. 1996. Equine piroplasmosis an update on diagnosis, treatment and prevention. Br Vet J. 152(2):139-51.

- Dewaal DT. 1992. Equine Piroplasmosis: a Review. Brit Vet J. 148(1):6-14.

- Maurer FD. 1962. Equine Piroplasmosis-Another Emerging Disease. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 141(6):699.

- Wise LN, Kappmeyer LS, Mealey RH, Knowles DP. 2013. Review of equine piroplasmosis. J Vet Intern Med. 27(6):1334-46.

- Wise LN, Pelzel-McCluskey AM, Mealey RH, Knowles DP. 2014. Equine piroplasmosis. Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract. 30(3):677-93.

- 2013. Equine piroplasmosis. OIE Manual of Diagnostic Tests and Vaccines for Terrestrial Animals. Chapter 2.5.8.

- Kappmeyer LS, Thiagarajan M, Herndon DR, Ramsay JD, Caler E, Djikeng A, et al. 2012. Comparative genomic analysis and phylogenetic position of Theileria equi. BMC Genomics. 13:603.

- Zobba R, Ardu M, Niccolini S, Chessa B, Manna L, Cocco R, et al. 2008. Clinical and laboratory findings in equine piroplasmosis. J Equine Vet Sci. 28(5):301-8.

- Ueti MW, Mealey RH, Kappmeyer LS, White SN, Kumpula-McWhirter N, Pelzel AM, et al.. 2012. Re-Emergence of the Apicomplexan Theileria equi in the United States: Elimination of Persistent Infection and Transmission Risk. Plos One. 7(9).

- Rashid HB, Chaudhry M, Rashid H, Pervez K, Khan MA, Mahmood AK. 2008. Comparative efficacy of diminazene diaceturate and diminazene aceturate for the treatment of babesiosis in horses. Trop Anim Health Prod. 40(6):463-7.

- Schwint ON, Ueti MW, Palmer GH, Kappmeyer LS, Hines MT, Cordes RT, et al. 2009. Imidocarb Dipropionate Clears Persistent Babesia caballi Infection with Elimination of Transmission Potential. Antimicrob Agents Ch. 53(10):4327-32.