Equine granulocityc anaplasmosis

Etiology

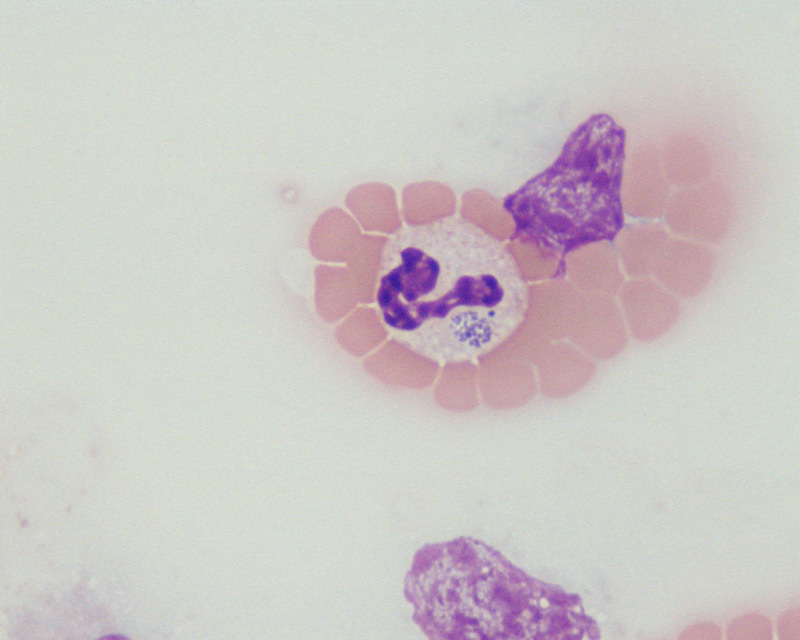

The etiological agent, formerly Ehrlichia equi, is now considered a strain of Anaplasma phagocytophilum due to their 99.1% homology on 16S sequence of ribosomic RNA. Cocobacillary, gram-negative, with a tropism for granulocytes, tends to aggregate within intracytoplasmatic vacuoles from 1.5 to 5 µm of diameter, creating morulae.

Epidemiology

Present in United States, Canada, Brazil, Europe, Africa and Asia, the disease occurs in the late fall, winter and spring. A. phagocytophilum causes clinical disease in domestic ruminants, equids, dogs, cats and humans and is transmitted by ticks from the Ixodes genus. In Europe, their hosts are wild rodents, sheeps and roe deers. Migrants birds play a role in A. phagocytophilum dispersion by disseminating the infected ticks. Equids are considered an aberrant host since the presence of bacteria is limited to the acute disease. The disease is usually subclinical in endemic areas which show higher seroprevalence, and may be concomitant with other diseases such as borreliosis and piroplasmosis.

Pathogeny

Once inoculated at the dermis by a tick bite, A. phagocytophilum is disseminated through the lymphatic vessels or the blood and invades the lymphoreticular and hematopoietic systems cells, where it replicates within vacuoles. The exact pathogenic mechanisms by which bacteria causes an inflammatory response locally and systemically at different organs as well as pancytopenia are poorly understood. This triggers suppression of host defences, increasing the predisposition to develop opportunistic secondary infections. Between days 19 and 81 after infection, cellular and humoral immune responses are developed, with the presence of antibodies that last for at least 2 years.

Clinical signs

The incubation period is usually less than 14 days. Clinical signs vary with age, being less severe in horses under 4 years. Clinical signs last from 3 to 16 days and the disease is often self-limiting in untreated animals. During the firsts days, fever is generally high (39.4-41.3ºC) and persists up to 14 days. Initial signs are reluctance to move, ataxia, depression, partial anorexia, jaundice and petechiae. By days 3-5 after infection, limb oedema, secondary infections, secondary trauma due to incoordination and rarely cardiac arrhythmias could develop. Laboratory abnormalities are leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, anaemia, jaundice and the detection of inclusion bodies or morulae within neutrophils and eosinophils in blood smears.

Diagnosis

Differential diagnoses of EGA include purpura hemorrhagica, liver disease, equine infectious anaemia, equine viral arteritis and encephalitis. Definitive diagnosis can be made taking into account the geographic area, clinical signs, laboratory findings and the observation of more than three morulae in blood smears stained with Giemsa or Wright’s stain. Serological analysis is carried out by indirect immunofluorescence. Several PCR are available for detection of A. phagotytophilum genogroup members, with high sensitivity and specificity that are of particular interest during early and final stages of disease. Macroscopic lesions observed are ventral abdomen and limb oedema and hemorrhages (petechiae and ecchymoses) in distal limbs. Histological findings are vascular inflammation at extremities, sexual organs, pampiniform plexus, kidneys, heart, brain and lungs.

Treatment

Oxytetracycline at 7 mg/kg SID for 5-7 days has demonstrated to be effective for EGA, with prompt clinical improvement. If untreated, the disease is usually self-limiting in 2 to 3 weeks. Supportive measures are recommended in severe cases including fluid therapy, limb wraps and stall confinement. Prognosis is excellent in uncomplicated cases.

Prevention and control

At present, there is no vaccine available. Prevention is limited to tick control measures by using permethrin based repellent products.

Public Health Considerations

A. phagotytophilum comprises multiple strains, some of which have zoonotic potential. Phylogenetic studies indicate that strains isolated from humans, dogs and horses in Europe belong to the same clonal complex. Furthermore, wild boars and hedgehogs are suspected to be hosts of the human variants. Still, few cases of human granulocytic Anaplamosis are reported, mainly for the unspecificity of clinical signs.

References

- Pusterla, N. and J. E. Madigan (2013). "Equine Granulocytic Anaplasmosis." Journal of Equine Veterinary Science 33(7):493-496.

- Stuen, S. (2007). "Anaplasma phagocytophilum-the most widespread tick-borne infection in animals in Europe." Vet Res Commun 31(1):79-84.

- Stuen, S., et al. (2014). "Anaplasma phagocytophilum-pathogen with a zoonotic potential." Parasites & vectors 7(1):O24.