Equine piroplasmosis

Etiology

Equine piroplasmosis (EP) is an infectious disease caused by the intraerythrocytic protozoan parasites B. caballi and T.equi. Previously, T. equi was known as Babesia equi. These parasites are transmitted by ixodid ticks of the genera Dermacentor, Hyalomma and Rhipicephalus; although iatrogenic transmission can also occur. In the case of T. equi, a placentary transmission has been described. Horses that survive can become inapparent carriers for a long time (4 years for B. caballi or lifelong for T. equi) and they can act such a source of infection for the ticks, which will parasite more horses. This disease is important since it is the main restriction on the export of horses to other countries.

Epidemiology

EP is an endemic disease present in tropical and subtropical regions. By contrast, Canada, Iceland, Australia and Japan are free countries currently. In the US, the infection would be limited to one or more areas.

B. caballi and T. equi present a indirect biological cycle. The cycle starts when sporozoites are transmitted through the infected tick saliva to the equid host. .

- B. caballi: sporozoites invade erythrocytes directly and they reproduce asexually first to trophozoites and then to merozoites. The merozoites continue to reproduce asexually causing the rupture and invasion of new red blood cells.

- T equi: sporozoites invade peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), they reproduce asexually first to schizonts and then to merozoites and they cause the rupture of these cells. The merozoites invade the erythrocytes, which continue to reproduce asexually and invade new red blood cells.

Pathogeny

EP is characterized by an haemolytic anemia, which results from the lysis of erythrocytes (due to merozoites multiplication) as well as from removal of infected erythrocytes by the spleen. It has been seen that nonparasitized erythrocytes are also eliminated, but the reason is unknown. Thrombocytopenia, alter coagulation, vasculitis, and formation of microthrombi within small vessels may also be observed. Transplacental transmission can result in abortions (late gestation most common), stillbirths, or birth of an infected foal, but not all foals from infected mares will be affected. Colostral antibodies against both parasites may persist in the foal for 4 to 5 months. Horses infected with T.equi produce antibodies against equi merozoite antigen (EMA-1) and those infected with B. caballi to rhoptry associated protein 1 (RAP 1).

Clinical signs

The clinical signs are variable and nonspecific. In general, the infection with T. equi results in more severe clinical disease than the infection with B. caballi. The presentation can be hyperacute, acute or chronic. The hyperacute form is rare and horses may be found dead. Signs of acute infection can vary from fever, anorexia, lethargy and peripheral edema to anemia, jaundice, tachycardia, tachypnea, hemoglobinuria and/or bilirubinuria, thrombocytopenia and petechiae on mucous membranes. Chronic infection may result in weight loss, lethargy, partial anorexia and splenomegaly on rectal palpation.

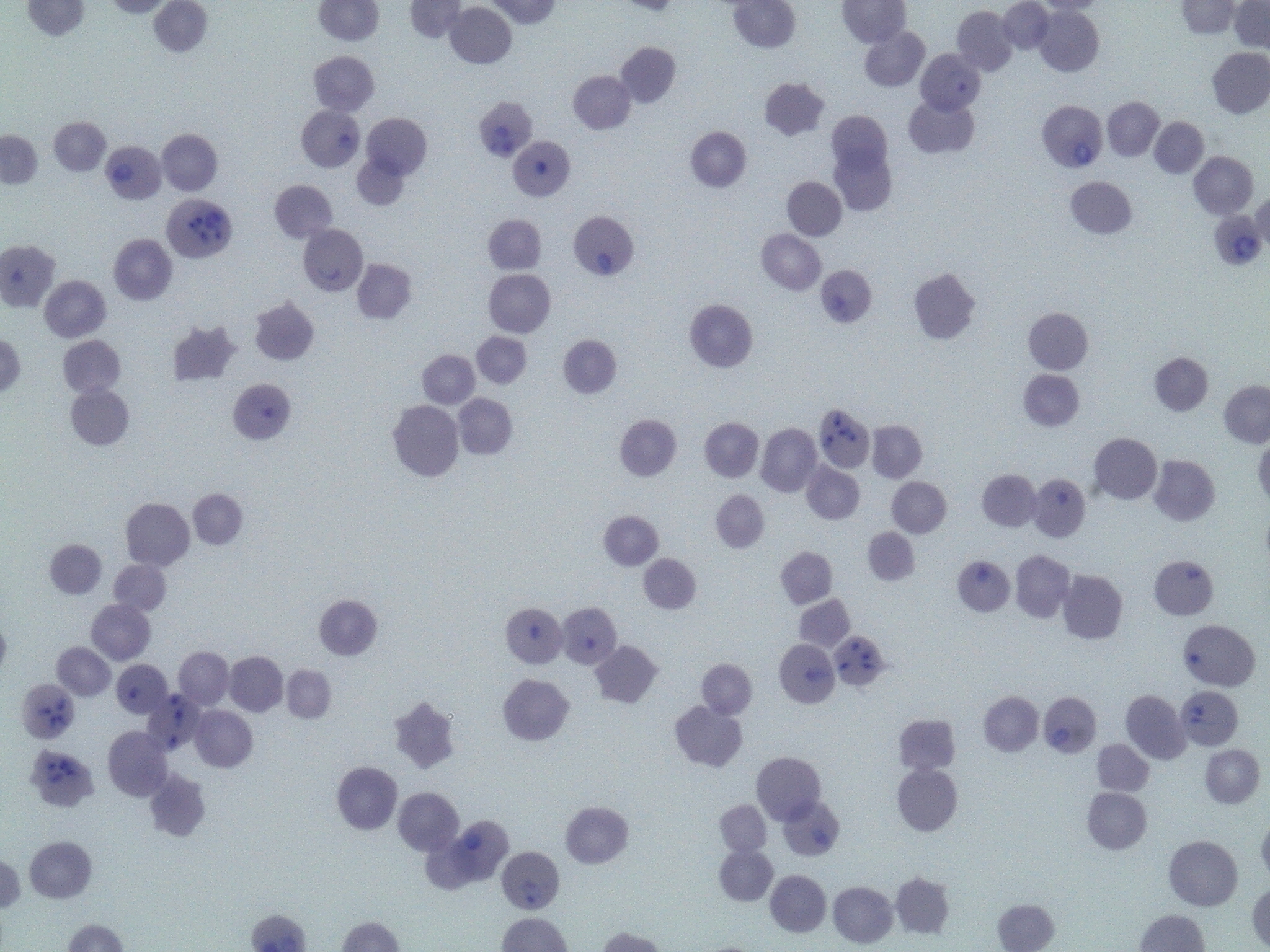

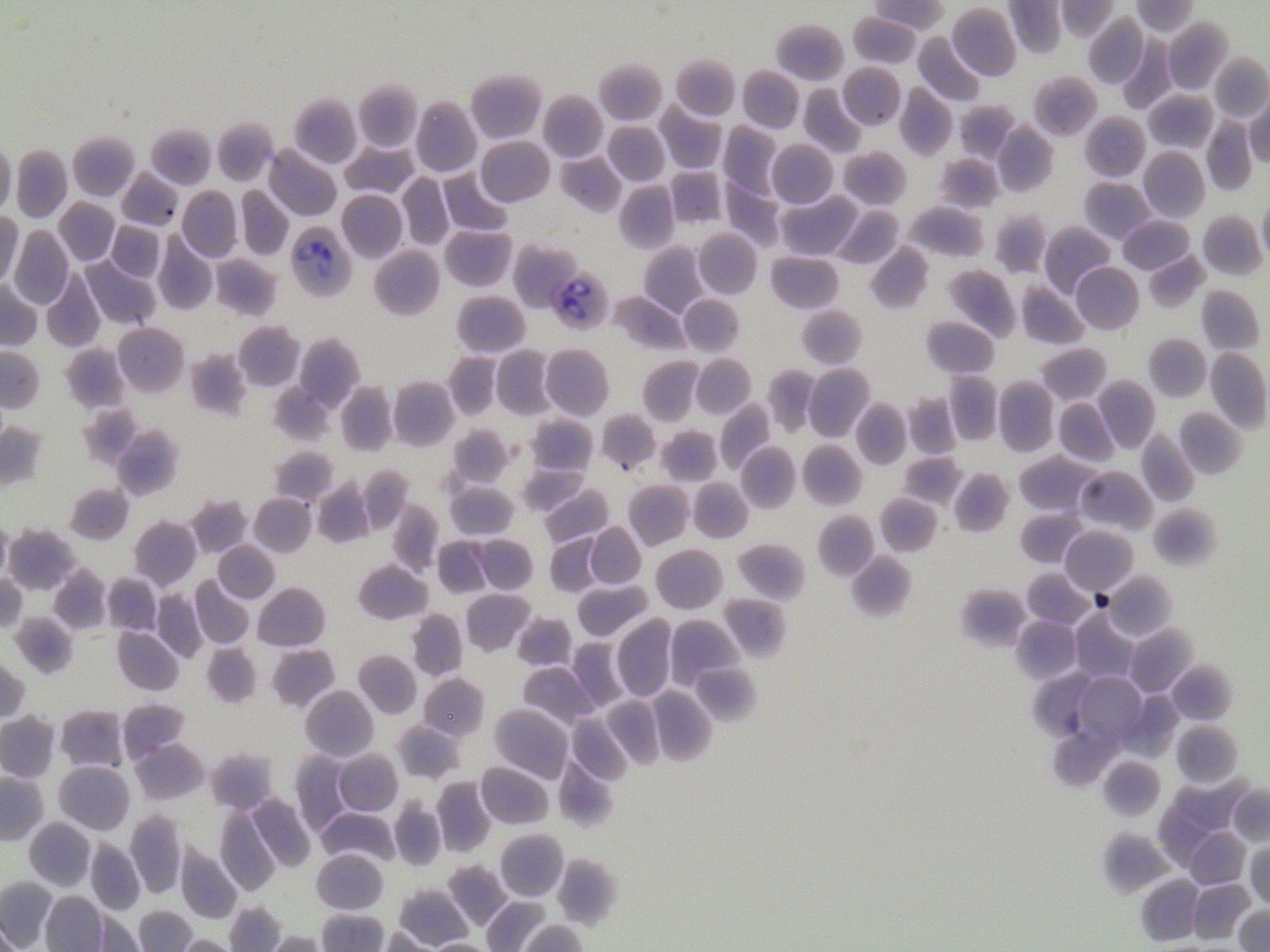

Diagnosis

During the acute state of the infection, EP can be diagnosed through a thin blood smear stained to identify the parasites within the erythrocytes (although this method has a low sensitivity), PCR and through several serologic tests such as the complement fixation test (CFT can detect seroconversion approximately 8 to 11 days after infection) and the indirect fluorescent antibody test (IFAT may detect seroconversion 3 to 20 days after infection). The competitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (c-ELISA) is considered to be the most sensitive test for chronic infection or identifications of carriers, detecting seroconversion 21 days after infection. In seropositive horses it would be ideal to carry out a PCR in order to determine the parasite load or if the horse has cleared the infection, since horses can remain seropositive long after eliminating the parasite: up to 8 months-1 year in B. caballi infections and up to 2 years in T. equi infections.

Treatment

Several drugs have proved to alleviate clinical signs, being imidocarb dipropionate (ID) administered intramuscularly, together with a correct hydration of the animal, the most effective against both parasites. ID has anticholinesterase activity, so reactions to the drug as sweating, signs of agitation, colic and diarrhea are often present. Antispasmodic drugs such as N-butil scopolamine or xylazine may be used prior to ID, and also analgesic and anti-inflammatory drugs such as Flunixin meglumine.

Other drugs used against equine piroplasmosis are diminazene aceturate and diaminazene diaceturate; upon administration they can cause severe muscle damage but they can be an alternative in pregnant mares.

There are differences in the treatment of both parasites with ID; often B. caballi requires two boosters at 2 mg/kg whereas T. equi may need up to 4 boosters at 4 mg/kg. Treatment of T. equi may also include oxytetracycline IV and buparvaquone, the latter is used for persistent infections.

Prevention and control

There are no vaccines available for these parasites. The regular evaluation of the animal, the elimination of the ticks and the use of acaricides can help to prevent the infection.

Public Health Considerations

Equine piroplasmosis is a non-zoonosic disease, but it is included in the OIE list of notifiable diseases.

References

- Equine Infectious Diseases. 2014 Elsevier Inc. ISBN: 978-1-4557-0891-8