Glanders

Etiology

Glanders is one of the oldest equine diseases with zoonotic potential, caused by Burkholderia mallei, a gram negative, non-motile, facultative intracellular, non-encapsulated and non-spore-forming bacillus.

Epidemiology

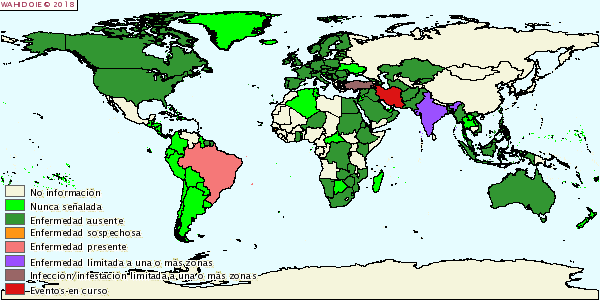

Principal hosts are Equidae family, humans and occasionally Felidae. Camels, bears, wolfs and dogs have demonstrated to be susceptible to glanders. Carnivores can get the disease by ingestion of infected meat. Small ruminants may be infected in contact with affected horses. Infection is produced through food or water contaminated with secretions from respiratory tract or skin ulcerated lesions. High animal densities and asymptomatic carriers favour the spread of the disease. Thanks to control and eradication programs, global prevalence of glanders has been significantly reduced and actually is localized in Eastern Europe, Middle East, Asia, Africa and South America.

Pathogeny

Incubation period may last from few days to many months. Horses are usually chronically infected, while donkeys and mules develop the acute form of disease. Human infection can happen through aerosol transmission from infected animals and used to be fatal if left untreated.

Clinical signs

There are three forms of glanders, depending on the location of the primary lesions, although they are usually shown combined: 1) Nasal: Nasal and upper respiratory tract nodules and ulceration with thick yellowish secretion that can resolve forming star-shaped scars, regional lymphadenopathy, fever, anorexia, cough and dyspnoea. 2) Pulmonary: Nodules within the lungs that can extend to liver, spleen and kidneys, fever, dyspnoea, cough and loss of body condition. 3) Cutaneous: Subcutaneous nodules over lymphatic vessels at limbs (hind), costal area and ventral abdomen, which become ulcerated, discharging a viscous yellowish exudate and occasionally orchitis may occur in stallions.

Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis with other infections as strangles, ulcerative lymphangitis, botryomycosis, sporotrichosis, pseudotuberculosis, epizootic lymphangitis, horsepox, tuberculosis and other pathologies like trauma an allergy. Complement fixation is the test prescribed by OIE for international trade. Other diagnostic tests available are bacterial identification through culture and staining, real time PCR identification; serologic tests like ELISA, immunoblot and Rose Bengal agglutination test; cellular inmunity mallein assay is useful in endemic areas. Macroscopic lesions depend on clinical presentation: in the nasal cavity, ulceration and regional lymphadenitis; at the lungs, nodules, consolidation and diffuse pneumonia; at the liver, spleen and kindeys, pyogranulomatous nodules may be observed; at the skin, nodules, ulceration, lymphangitis and orchitis.

Treatment

Antibiotic prophylaxis has been used in endemic areas, which leads to carrier animals that can spread the disease, therefore this practice is not recommended.

Prevention and control

Glanders is considered a reportable disease by the OIE. Prevention and control of this disease is based in early detection programs and humanitarian elimination, strict animal movement controls, establishment of quarantines and cleaning and disinfection of outbreak areas. There is no vaccine for glanders in animals.

Public Health Considerations

Glanders is rare, but is considered a serious zoonotic disease. Reported human cases have been caused by direct contact with animals or laboratory exposure. Mortality can reach 95% if cases are untreated. Actually, a vaccine for people is being developed for the possibility that this organism becomes an instrument of bioterrorism.

References

- Equine Infectious Diseases. 2014 Elsevier Inc. ISBN: 978-1-4557-0891-8.

- OIE, Ficha técnica de la enfermedad.