Potomac horse fever

Etiology

Potomac equine fever is an equine infectious disease caused by Neorickettsia (formerly Ehrlichia) risticii, an obligate intracellular Gram-negative bacterium of the Anaplasmataceae family (Rickettsiales order and Neoricketssia genus) described in 1984 in the United States.

Epidemiology

The only studies in which the prevalence of N. risticii has been evaluated were carried out in the USA, where it is endemic. In 1996, Atwill and others obtained a 7% prevalence in unvaccinated horses in the state of New York. In California, Pusterla and others (2000) found a seroprevalence of 15%. Other studies conducted in Ohio, Minnesota and Illinois reported seroprevalences of 13%, 24% and 26%, respectively. Isolated cases have also been described in Canada, South America and Europe. The bacterium has also been isolated in cats, dogs, goats, pigs and mice, although in these species, the disease is subclinical. Potomac fever has a seasonal character, ocurring mainly in summer and early autumn, together with the greater proliferation of potential vectors.

Pathogeny

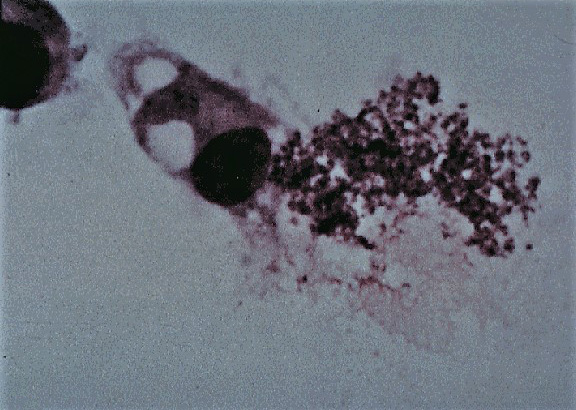

The biological cycle of the bacteria that causes Potomac fever is not completely known, although it seems that the main vector is a trematode infected with N. risticii. The trematode infects aquatic snails and ends up returning to the water where it is ingested in turn by the larval stages of numerous aquatic insects such as those of the Orders Trichoptera, Ephemeroptera, Odonata and Zygoptera. It is believed that the infection of horses is due to the accidental ingestion of adult insects that harbor N. risticii in the metacercaria phase of a trematode and that they fly inside the stables or in the pastures. The bacterium causes acute enterocolitis in horses, in which it is usually located inside blood monocytes or lymphoid tissue macrophages. Transmission by direct contact or by other vectors such as ticks or fleas has not been demonstrated, as in other species of the Anaplasmatacea family. Transplacental transmission has been demonstrated experimentally. The experiment was carried out in a group of pregnant mares, producing abortions in a high percentage of them. The abortion is late term (from 100 days post-infection). The foals born from the infected mares have antibodies against N. risticii.

Clinical signs

The infection is characterized by the appearance of slight depression and anorexia followed by fever (38.9-41.7 °C). In this stage, bowel sounds may be reduced. After 24-48 hours, moderate or severe diarrhea may occur in 60% of infected horses, which is usually accompanied by moderate abdominal pain. Some horses may develop severe signs of infection or dehydration. The signs may be indistinguishable from those caused by other bacteria that cause enterocolitis. Laminitis can occur in 20-30% of horses. The haematological findings are variable, being able to be normal in the initial phases or appear leukopenia (neutropenia and lymphopenia) and thrombocytopenia. Leukocytosis is frequent once the infection is advanced. At necropsy, horses have enterocolitis and diffuse inflammation mainly of the large intestine. The mortality ranges between 5 and 30%.

The infection of the fetus in pregnant females can trigger abortion, which can be accompanied by placentitis and placental retention. Aborted fetuses may have colitis, periportal hepatitis and lymphoid hyperplasia in the mesenteric lymph nodes and the spleen.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis based on the presence of clinical signs and epidemiological aspects such as seasonality and geographical location is not definitive. To confirm the infection, it is necessary to isolate or detect N. risticii in blood or feces of horses by culture or PCR. The culture does not usually become routine due to its difficulty and slowness. There is a real-time PCR that allows the detection of the DNA of the bacteria in less than 2 hours in blood and feces samples (ideally in both simultaneously to increase sensitivity) and is usually the most used option.

The diagnostic value of serology is limited although some horses may have high titers at the time of infection. In fact, there are usually many cases of false positives in serological tests, which makes diagnosis with indirect techniques difficult.

Treatment

Horses infected in recent stages can be treated successfully using oxytetracycline (6.6 mg / kg IV). The response to treatment is usually observed within 12 h by a decrease in rectal temperature followed by an improvement in the rest of the associated clinical signs. If the therapy is started soon, the signs may disappear on the third day of treatment and it is not usually necessary to extend the treatment beyond 5 days. In animals that show enterocolitis, it is necessary to administer fluid therapy treatments. Laminitis, when it appears, is severe and is usually refractory to treatment.

Prevention and control

There are several commercial inactivated vaccines. Studies carried out on experimentally infected animals suggest a vaccine efficacy of around 78%, although in field conditions it could be lower. Vaccination failures are mainly attributed to the limited role of antibodies in protection. The most important preventive measures can be to avoid endemic areas, the sanitation of water and drinking fountains and the establishment of measures to avoid the presence of insects in the stables.

Public Health Considerations

Potomac equine fever is not a zoonosis.

References

- Atwill ER, Mohammed HO. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1996 Apr 15;208(8):1295-9. Benefit-cost analysis of vaccination of horses as a strategy to control equine monocytic ehrlichiosis.

- Bertin FR, Reising A, Slovis NM, Constable PD, Taylor SD. Clinical and clinicopathological factors associated with survival in 44 horses with equine neorickettsiosis (Potomac horse Fever). J Vet Intern Med. 2013 Nov-Dec;27(6):1528-34. doi: 10.1111/jvim.12209. Epub 2013

- Heller MC, McClure J, Pusterla N, Pusterla JB, Stahel S. Two cases of Neorickettsia (Ehrlichia) risticii infection in horses from Nova Scotia. Can Vet J. 2004 May;45(5):421-3. PubMed PMID: 15206592; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC548627.

- Potomac horse fever. AAEP Infectious Disease Guidelines.

- Potomac horse fever. Digestive System, MSD Veterinary Manual.

- 6: Pusterla N, Johnson E, Chae J, Pusterla JB, DeRock E, Madigan JE. Infection rate of Ehrlichia risticii, the agent of Potomac horse fever, in freshwater stream snails (Juga yrekaensis) from northern California. Vet Parasitol. 2000 Sep 20;92(2):151-6. PubMed PMID: 10946138.

- Ristic M, Holland CJ, Dawson JE, Sessions J, Palmer J. Diagnosis of equine monocytic ehrlichiosis (Potomac horse fever) by indirect immunofluorescence. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1986 Jul 1;189(1):39-46. PubMed PMID: 3525479.

- Xiong Q, Bekebrede H, Sharma P, Arroyo LG, Baird JD, Rikihisa Y. An Ecotype of Neorickettsia risticii Causing Potomac Horse Fever in Canada. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2016 Sep 16;82(19):6030-6. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01366-16. Print 2016 Oct. PubMed PMID: 27474720; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5038023.